|

YOGA |

|

|

LAURANCE JOHNSTON, PH.D. |

|

As a “maturing” baby

boomer sitting too much at the computer, I find my body has become

creaky. Rather than just chalking up my inflexibility to aging’s

inevitable entropy, I recently started yoga. Although once fairly

athletic, I have found the experience humbling and need a variety of

assistive devices to assume basic poses that many in the class -

especially the women - can readily do.

Reflecting on my

difficulties relative to the much greater physical limitations

associated with spinal cord injury (SCI) and wheelchair living, I

initially thought that yoga would not be a good topic to cover. My

research indicated otherwise, however. People with physical disabilities

can accrue much benefit through yoga.

As a part of this

research, I read a book written by Matthew Sanford, a 40-year-old yoga

instructor who sustained a thoracic (T4-6) injury from a 1978 roll-over

auto accident. At Minnesota’s Courage Center, Sanford teaches yoga to

others with disability, including SCI (all levels), MS, cerebral palsy,

spina bifida, head injury, and stroke.

His book, Waking:

A Memoir of Trauma and Transcendence (2006) is one of the best books

on disability I have read. In it, he describes how learning yoga helped

him to transcend his injury through better mind-body-spirit integration,

and to energetically reconnect to paralysis-affected body parts.

After reading his

book, discussing yoga with him, and observing his class, I now believe

when adapted to the needs of individuals with physical disabilities and

with appropriate assistance, yoga is a valuable healing tool with much

to offer. According to Sanford, yoga principles do not discriminate due

to disability. Basically, the needed adaptations for disability are just

a greater expression of what I require due to middle-age inflexibility.

Unfortunately, although yoga instructors have a good idea of the

adaptations I need, relatively few appreciate the adjustments required

for significant physical disability. Therefore, one of Sanford’s

priority goals is to create and disseminate educational programs that

will better integrate yoga and disability.

Sanford emphasizes

you must have realistic expectations when starting yoga. He is, indeed,

still paralyzed after years of practice. However, he has gained a much

greater sense of a mind-body alignment, which he calls presence. Sanford

believes we define sensation too narrowly, in part, because we defer too

much to the limiting opinions of healthcare experts rather than

cultivating and listening to the voice from within. By so doing, we shut

off the subtle lines of communication that remain after injury. Yoga

helps us hear and reestablish the link to the inner voice again.

In his book, Sanford

specifically describes this re-linking: “yoga instruction rekindled a

feeling of energetic sensation within my mind-body relationship…I grew

in dimension and my entire body began whispering to me once

again, albeit in a more eloquent voice.”

Sanford believes

many possibilities other than walking exist for healing within the

mind-body relationship. Due to yoga, Sanford has become more present in

his body, senses more clarity in his spine (focal point of yogic

awareness) as he moves, is more grounded and balanced. His overall

strength and movements have an improved “bang for the buck.” Together

these results can produce many life-enhancing benefits for those with

SCI, including, for example, more efficient transfers, improved

bowel-and-bladder sensation, sexual function, etc. Finally, although

downplaying the possibility, by getting more life-force energy once

again moving through areas of paralysis-associated energy stagnation,

yoga may, indeed, cultivate an environment more conducive to

physiological regeneration.

From personal

experience, Sanford cautions yoga students with SCI to be patient and

not force progress. He states: “Every student – whether disabled or not

– must practice non-violence with his or her yoga practice.”

Unfortunately, Sanford learned the hard way; early in his practice, he

broke his leg due to his eagerness to assume an advanced lotus position.

It was a mistake he does not want to pass on.

SCI ADVANTAGE

Yoga is a

mind-body-spirit discipline whose more familiar physical poses represent

the lower rungs of a ladder leading to enhanced awareness of our greater

spiritual nature. Yoga’s Sanskrit root implies a yoking or union of the

individual to universal self. In this regard, in spite of yoga’s

physical demands, people with SCI may actually have some advantage in

climbing up the ladder.

In a crude analogy,

this ability is like hearing a whisper in a raucous bar. Because there

is so much distraction - loud conversations, ringing cell phones,

rock-and-roll music, cigarette smoke, good-looking women – it’s hard to

hear the whisper. Under yoga metaphysics, this subtle whisper represents

a higher version of who we are, and, because it is all-pervasive,

extending beyond the bar to the entire neighborhood, a connection to our

greater universe: the true source of all individual strength.

According to

Sanford, people living with SCI do not have the same gross-body

distractions, allowing them to delve deeper into the core of yoga. By

muting the sensory overload, his injury facilitated a greater connection

to the life-sustaining whisper that flows through his body, a connection

which most able-bodied students strive to achieve. In his case, Sanford

states “Meditative attention amplifies it to the point of exaggeration;

and engaging social interaction pushes it into the distant background; a

rock concert makes it disappear completely.”

Comparing his

paralysis-affected physicality to an artichoke’s outer layer, he notes:

“I received something in exchange for absorbing so much trauma at age

thirteen. I experienced a more direct contact presence of consciousness

– the heart of the artichoke. Although my life has taken much away, it

has also revealed a powerful insight.”

|

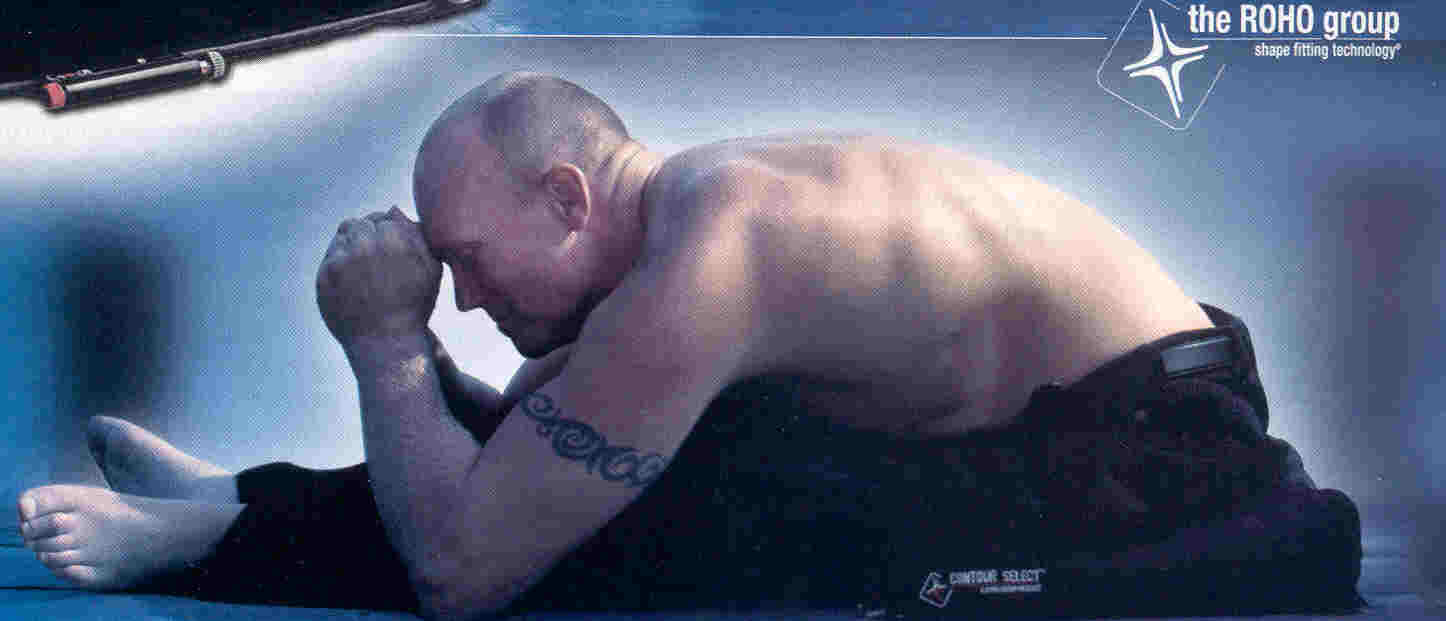

How Yoga

Helps Me

I came to Iyengar yoga twelve

years after my original injury because I missed my body. I had

reached a point where living as if I was only a floating upper

torso was no longer tolerable. I had grown weary of willfully

dragging my paralyzed body through my life. I wanted to

reconnect, to feel my entire body again in whatever way was

still possible. I figured what better way to start than a

four-thousand year old discipline that is expressly dedicated to

the integration of mind, body, and spirit.

Now, sixteen years later, I have

a vibrant sense of my whole self that I never believed was

possible. The disciplined practice of yoga has shown me the

subtle, energetic connections that exist between mind and body.

These connections are never going to make me walk again, but

they offer a sense of wholeness and vitality that inform every

aspect of my life. I can be "present" within both the paralyzed

and unparalyzed parts of my body. This realization has given me

a profound sense of inward freedom. I wish the same for

everyone.

-Matthew Sanford, January 2007 |

BODY ELECTRIC

By learning to sense

the subtle whisper through ongoing yoga practice, Sanford connects to

his paralyzed limbs without going though a hard-wired, neuronal

connection. Basically, the whisper is mediated through his body’s

electromagnetic nature. So to speak, Sanford receives information from

paralyzed limbs through radio waves rather than a telephone wire (i.e.,

neuronal connections). The transmitted information may be more subtle,

but, as receiving ability is developed, it becomes increasingly rich in

informational content – like the difference between crude Morse code and

a TV signal.

Scientists

increasingly believe that we are fundamentally electromagnetic beings.

Every molecule, cell, and organ emits electromagnetic vibrations, often

assessed through medicine’s many electronic devices (e.g., MRIs, EEGs,

etc). From a stress-related heartbeat to anxiety-generated brainwaves,

the nature of our life is a cumulative manifestation of our

electromagnetic eddies and flows and how we allow them to be influenced

by our environment.

In yoga, our

electromagnetic nature is further defined through the downloading of

life-force energy prana through vortexes called chakras.

In turn, this super-refined energy is circulated throughout the body

through thousands of energy channels, called nadis, that parallel

anatomical structures and are somewhat comparable to acupuncture

meridians.

Especially relevant

to SCI, the body’s foremost channels are the Shushmana, located

in the spine’s central column (an ene rgetic counterpart of our spinal

cord) and the Ida and Pingala channels (the energetic

equivalent of nerve plexuses that radiate out from the cord) that

crisscross through the Shushmana. The caduceus, medicine’s foremost

symbol in which two snakes intertwine around a staff, is a

representation of these life-force channels. Although beyond the

article’s scope, learning to correctly move energy through these

spinal-cord-related channels through advanced yogic practices (called

Kundalini) can mitigate SCI’s impact. rgetic counterpart of our spinal

cord) and the Ida and Pingala channels (the energetic

equivalent of nerve plexuses that radiate out from the cord) that

crisscross through the Shushmana. The caduceus, medicine’s foremost

symbol in which two snakes intertwine around a staff, is a

representation of these life-force channels. Although beyond the

article’s scope, learning to correctly move energy through these

spinal-cord-related channels through advanced yogic practices (called

Kundalini) can mitigate SCI’s impact.

Basically, like

turning up a spigot’s water pressure or taking the crimp out of the hose

that blocks the flow to the garden, yoga enhances vital-force flow

throughout the body and, in turn, the physiological functions that

support health, such as blood circulation and nervous-system

conduction.

KEY YOGA

PRACTICES

Because yoga is a

rich discipline, key practices can only be briefly highlighted, and, as

such, interested readers should consult the listed resources.

Asanas:

Yogic poses, called asanas, are key tools to obtaining benefits,

ranging from the physical to spiritual. Evolving over the millennia,

standing, sitting, bending, twisting, and reclining poses have been

developed to enhance function in every body part.

Various

poses, especially in combination, are prescribed for diverse ailments,

including those involving heart and circulation, respiratory, digestive,

urinary, hormonal, immune, and brain and nervous systems. Various

poses, especially in combination, are prescribed for diverse ailments,

including those involving heart and circulation, respiratory, digestive,

urinary, hormonal, immune, and brain and nervous systems.

Due to his

paralysis, Sanford initially emphasized traditional sitting poses. While

practicing the Maha Mudra pose, he had an energetic breakthrough:

“As I move into this pose, something clicks or snaps into place or

becomes manifest …I suddenly feel a tangible sense of my whole body –

inside and out, paralyzed and unparalyzed. I am stunned.”

Unlike able-bodied

people who attempt to physically align themselves with the pose and then

perhaps feel the energy, Sanford teaches “backwards yoga” to students

with disability. Basically, if he feels the right energetic resonance,

he attempts to trace this energetic core back into the physical and

outward through his paralyzed body.

Pranayama

combines two words: prana, life-force energy, and ayama,

the storage or distribution of that energy. Pranayama focuses on

conscious breathing and its link to mind and body; it cultivates

life-enhancing flow of prana through the body. Because poses

remove flow-impeding barriers, pranayama’s benefits are best achieved

after the poses have been mastered. Control of inhalation, exhalation,

or breath retention influences the nervous system in different ways.

Due to its power, pranayama should be practiced under the supervision

of an experienced yoga teacher.

Meditation:

Often done in conjunction with

poses or breathing exercises, meditative practices help turn off life’s

sensory cacophony and the ensuing monkey-mind in which thoughts

constantly bounce around our consciousness. As a result, we tune into

and become more aware of our nurturing inner whisper.

Once an individual

with SCI learns the various practices by working with a good teacher,

his program should incorporate solo sessions. This allows one to tune

into the inner whisper; and, as a result, connecting to, bringing to the

surface, and better understanding deeply ingrained, subconscious

beliefs, assumptions, or issues about the injury that may inhibit

healing.

For example,

Sanford’s yoga practice triggered “body memories” that helped him

further understand forgotten circumstances surrounding his car accident.

This ultimately led him to a deeper sense of freedom within his

mind-body relationship.

IYENGAR YOGA

Sanford teaches

Iyengar yoga developed by yoga master B.K.S Iyengar. A derivation of

traditional yoga, Iyengar yoga emphasizes alignment and precision in

poses adapted to individual needs. This is facilitated through the use

of props as needed, such as wooden blocks, folded blankets, straps, etc.

Individuals with SCI who are considering yoga should attempt to find an

instructor well versed in this tradition.

CONCLUSION

Yoga has much to

offer in this modern, multitasking, sensory-overload age, especially for

individuals with SCI. By cultivating a better presence in the entire

body, yoga will cumulatively produce benefits that will greatly enhance

quality of life.

Adapted from an article appearing in the April

2007 Paraplegia News (For subscriptions, call 602-224-0500 or go

to

www.pn-magazine.com).

|

RESOURCES

Khalsa SK.

KISS Guide to Yoga. DK Publishing, 2001.

Gach MR.

Acu-Yoga. Japan Publications, 1981.

Iyengar BKS.

Yoga: The Path to Holistic Health. DK Publishing, 2001.

Raman K.

A Matter of Health: Integration of Yoga and Western Medicine for

Prevention and Cure. EastWest Books 1998.

Sanford M.

Waking: A Memoir of Trauma & Transcendence. Rodale, 2006.

Sivananda

VS. The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga. Three Rivers

Press, 1995.

www.matthewsanford.com – Emphasizes adapted yoga for disability. |

TOP |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|